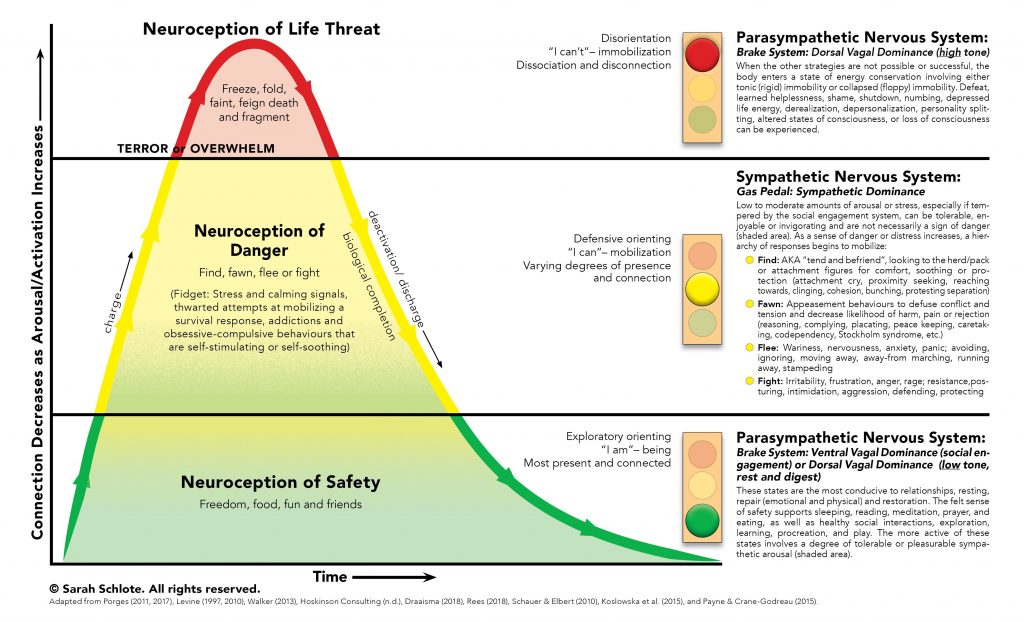

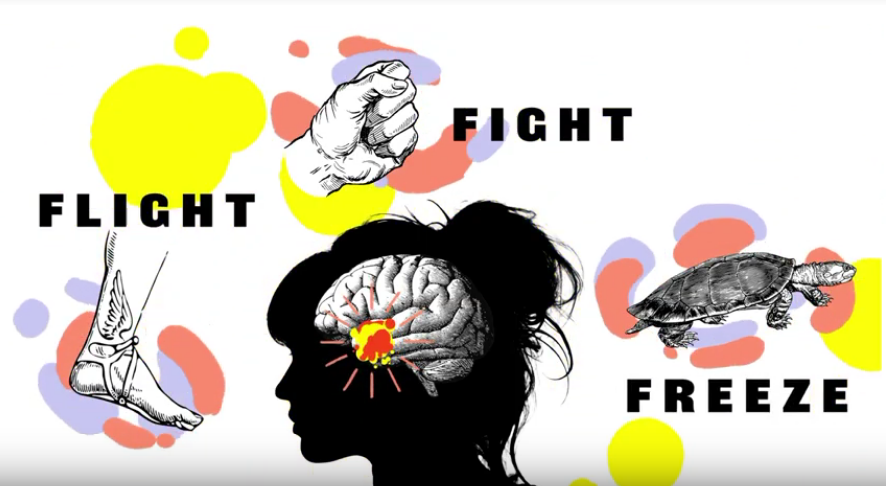

The human body has evolved to protect itself from danger. The acute stress response, also known as the “fight or flight” response, describes the body’s physiological reaction to a perceived threat. In response to acute stress or danger, the body’s sympathetic nervous system is activated by the sudden release of hormones. In turn, the adrenal glands secrete hormones, including adrenaline and norepinephrine, which prepare the body for immediate action to fight off a predator (“fight”) or flee from danger (“flight”). The “fight or flight” response involves physiological symptoms intended to facilitate fighting or fleeing (e.g., rapid heartrate, increased blood pressure, increased oxygen flow to major muscles, often leading to shaking or muscle tension) as well as an alteration in psychological state associated with the perception of threat (anxiety, panic, aggression, violent impulses).

The third component of the acute stress response involves “freezing,” or defensive immobilization. This response may occur when a danger is perceived as life-threatening and inescapable. Think of a deer frozen in the headlights, or a cockroach on its back feigning death. A human victim of a physical attack or sexual assault may go still and limp rather than fighting back. The freeze response may, in some cases, allow the victim to survive, and in other cases, the numbness that accompanies it may spare the victim pain in his final moments of life.

Thousands of years ago, in our ancestral environment, we faced daily threats to our survival: saber-tooth tigers, wooly mammoths, cold, hunger, warring tribes. The acute stress response was essential to our survival. In today’s world, most triggers for anxiety are more subtle: public speaking, taking the SATs, career uncertainty, financial stressors. But our bodies don’t know the difference: the physiological and psychological responses are the same today as they were tens of thousands of years ago.

The fight, flight, and freeze responses are activated instantly and without conscious choice. Remember, these immediate reactions have evolved to protect us from danger in circumstances in which stopping to think could cost us our lives. We do not choose what our bodies perceive as dangerous or which branch of the acute stress response is activated.

Most people who suffer from anorexia nervosa have extreme fears of food, weight gain, or both. People with active anorexia nervosa who have not yet begun the recovery process are able to keep their fears within manageable limits through avoidance: avoiding “fear foods,” avoiding feelings of fullness, avoiding weight gain, avoiding the scale, avoiding the wrath of the anorexic voice by engaging in compensatory behaviors.

Recovery from anorexia nervosa requires sufferers to face these fears head-on multiple times every day. For these reasons, the bodies of people recovering from anorexia nervosa are locked in a near-constant acute stress response for months. This is why people recovering from anorexia nervosa usually feel much worse during treatment than they felt while they were acutely ill. The fight, flight, freeze response also explains most of the extreme and perplexing behaviors that we see in those who are recovering from anorexia nervosa.

The “fight” response is directed at the perceived source of threat. For a person with anorexia nervosa, the source of threat may be the person who serves him food (e.g., a parent), a treatment provider who requires weight gain (e.g., a therapist, physician, or dietitian), or the person’s own changing body. Therefore, it is common for people recovering from anorexia nervosa to physically or verbally attack their parents, to lash out at their treatment providers, and to turn their rage inward toward their own bodies as manifested by self-hatred, self-injury, or suicide attempts. Food itself is also a perceived source of threat. The fight response towards food may manifest physically as throwing food, cups, or plates; or it may manifest emotionally as a subjective feeling of hatred towards food.

The flight response in anorexia nervosa involves escaping the perceived source of threat. Many people with anorexia nervosa run away from the table at meal or snack times, lock themselves in their rooms, or run away from home for hours or days at a time to avoid eating. Some people jump out of moving cars, leave treatment appointments prematurely, or run away from treatment centers. In a more subtle manifestation of the flight response, many people with anorexia nervosa do their best to avoid the caregiver who is most firm about requiring full nutrition, and gravitate towards caregivers who are more lenient.

The “freeze” response entails some form of inaction or shutting down. For example, many people exhibit an inability or apparent refusal to speak about food, weight, or anorexia nervosa. Others have difficulty swallowing food. Some people freeze at mealtimes, unable or unwilling to pick up a fork or spoon for hours on end. In some cases, this acute food refusal necessitates spoon feeding or tube feeding. Some people with anorexia nervosa appear dissociated, “frozen,” or “zoned out” at mealtimes or at other times when the anorexic voice is particularly powerful. It is common for patients with anorexia nervosa to shut down during therapy appointments, avoiding eye contact and not engaging in conversation with their treatment providers.

These fight, flight, and freeze behaviors are extremely distressing for sufferers and for the loved ones who are supporting them. If you are supporting a family member through recovery from anorexia nervosa, please know that your loved one has not chosen to act or feel this way. These behaviors are extremely common, and temporary, reactions to the severe anxiety brought on by facing one’s worst fears multiple times per day. The fact that your loved one is exhibiting these acute stress responses is proof that his or her fears are being challenged. In fact, if the acute stress response is not being activated, there is a good chance that the anorexia nervosa is not being sufficiently challenged, which may result in a protracted course of illness and a delay in recovery. Remember to stay the course, to continue requiring full nutrition, prompt and complete weight restoration, and psychological support, regardless of the acute stress responses that come about.